From the February 1920 issue of The American Magazine:

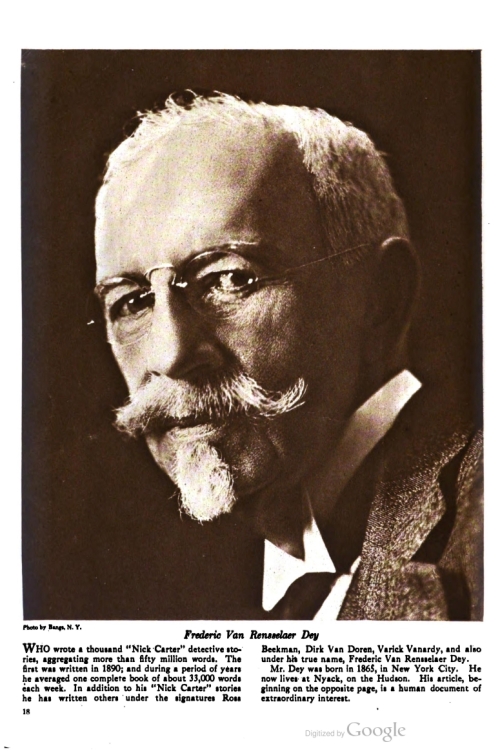

Frederic Van Rensselaer Dey

Who wrote a thousand “Nick Carter” detective stories, aggregating more than fifty million words. The first was written in 1890; and during a period of years he averaged one complete book of about 33,000 words each week. In addition to his “Nick Carter” stories he has written others under the signatures Ross Beekman, Dirk Van Doren, Varick Vanardy, and also under his true name, Frederic Van Rensselaer Dey.

Mr. Dey was born in 1865, in New York City. He now lives in Nyack, on the Hudson. His article, beginning on the opposite page, is a human document of extraordinary interest.

How I Wrote A Thousand “Nick Carter” Novels

By Frederic van Rensselaer Dey

Author of “Nick Carter, Detective”

This is not a “detective story.” It is an autobiographical sketch of a Detective of Fiction in the making and in the development. In this writing I confess to egoism; but I ask acquittal of egotism. I refer to the second definition of each word in the Century Dictionary. The true tale cannot be told without the emphasized I. Modesty is shut out. Such is the Editor’s sine qua non. “Go to it, sez ‘e.” I go.

Nick Carter came into “being” at a luncheon table in a down-town club. Figuratively, he sat down beside us. We were three, at the table: O. G. and G. C. Smith, of the firm of Street & Smith, publishers, and I — until Nick made a fourth.

He became “real” to me at that moment. From that moment I chummed with him, lived with him day and night (with few and short hiatuses) for nearly a quarter of a century.

Boiled down to one sentence the proposition made to me, was: “Can you write an acceptable thirty-three-thousand-word story a week around one character, and keep it up indefinitely?”

I replied that I could. And I did it. One can always do a thing if one thinks of it as an accomplished fact. It is not enough to believe that one can do it, and to try to do it under such restriction. One must think of it as already done.

“Prove it by writing ten of them in ten weeks,” said S. & S.

I sent the firm a list of ten titles (for advance advertising) within a day or so. I wrote and delivered four of the stories within three weeks. It was then decided to reduce the length to twenty thousand words. So I cut those four to that length, and wrote and delivered the remaining six, all within seven weeks from the start. I did not use a typewriter, then. I wrote with a short-handled stub gold pen. I should say, here, that the Nick Carter stories were kept at twenty thousand words only a short time. They were presently lengthened to thirty thousand, and subsequently restored to the original length — thirty-three thousand.

I do not now recall the exact number of Nick Carter stories I have written — call it approximately a thousand — and don’t run off with the notion that I wrote all of the published Nick Carters. One of my early stunts was to train other writers to do them, so that I could also supply Nick Carter serials (eighty thousand words and up) for the “New York Weekly,” a story paper. It was the regular thing to begin publication of these serials before I had completed the writing. And it was a common incident (while a story was running in the “Weekly”) to receive instruction like this from the firm: “Don’t end ‘Tracked Across the Atlantic’ with the fifteenth instalment. Keep it going till further orders.” (Instalments were six thousand words each. One serial instalment a week, in addition to a “Nick Carter Library,” which was then the name of the regular Nick Carter publication.)

You can see why it became necessary to “train” additional writers for the regulars. I did all of the serials until Frederick W. Davis was discovered. Ultimately he relieved me of them. I take off my hat to him. He was (and is) as good as I at words. Sometimes (I thought) better, although he never worked as fast. And there were Tozer, and Hooke, and Derby, and Phillips, and others, who wrote few, or many.

Let me hark back to that luncheon: An important thing to consider was the selection of a name for our detective. Mr. O. G. Smith had already made that selection, tentatively — provided it appealed to me, who was to write the stories. One of their writers, John R. Coryell by name, had written two stories for the firm in which he had named one of his characters Nick Carter, a son and pupil of Seth Carter, an “old detective.” The name pleased Mr. Smith, and I fell for it.

To that extent, Coryell created Nick Carter. But, I took him when he was a kid, educated him, developed him, brought him up, made a man of him, directed his destiny through many millions of print and circulated copies of the stories about him, and carried him into a dozen languages in translation.

The first actual Nick Carter story published was entitled “Nick Carter, Detective; by A Celebrated Author.” I wrote it. The firm chose the “Celebrated Author” moniker; not I. Possibly S. & S. had, then, a prophetic vision of Nick’s future celebrity.

Anyhow, I am the author of Nick Carter. I have written millions of words about him. But I never wrote one that could not have been read aloud to a Bible class without shocking it. I never permitted him to lie, nor to condone a lie. I made it a point with him always to seek the good qualities in men and women, and to overlook the distorted ones when possible and consistent. He never (in my writing) made use of a profane or vulgar word, nor permitted it if he could stop it. He discovered, among the byways of life, Chick, and Patsy, and Ten-ichi, and Peter, and Joseph, and Ida Jones, and Adelina, and Mrs. Peters, and made upright, God-fearing men and women of them. He always kept his word. He never touched liquor, nor permitted his assistants to do so. He respected all womankind under all conditions; in reverence for the memory of his mother.

I made Nick Carter my ideal of all that is good and right and truthful and honorable and upright and just, in ideal manhood. All writers, I think, in their heroes visualize and oralize an impossible but ideal self.

Understand, first, that Nick is much more real to me than are a majority of the persons who actually exist within my environment. Any casual acquaintance, whilom friend, or whimsical associate, is more fictitious than he is — to me. I have lived with him, slept with him, eaten with him, dwelt with him constantly through many years of comprehension and understanding. He has been ever a harsh, unbending mentor and critic, never a sympathizer. Sympathy from a friend, and self-pity from the ego, are character’s deadliest poisons.

I had only an introduction to him that day at luncheon. He came away from it with me. I was eight days writing the first story; we were getting acquainted. I wrote the second one in five days; the third, in four; the fourth, in three. Thirty-three thousand words (by column measure) each. Then, I cut the four to twenty thousand and wrote the fifth, in a week. After that, I rarely took more than three days to a story, and I wrote very many of them (while they continued at twenty-thousand-word length) in two days, always with my little stub gold pen. (l have it yet.) When they were lengthened again to thirty and thirty-three thousand, I worked three, sometimes four, days in the week, and played (sailed, and rowed, and fished at Sunapee Lake, New Hampshire) the other three. When the serials began, it added six thousand words a week to my stunt. I did it for a while, and then shouted for help! Not so much because of the extra words, as because it meant keeping the serial going (one story) while eight, ten, twelve, or more, distinctly different stories were being written at the same time. But I never did get mixed, and I have never been charged with repeating or plagiarizing myself …. More ego! But it’s true.

How did I do it? Well, let’s see. There were a lot of things which had to do with the doing.

First, I loved the work, enjoyed it. Aside from the mere labor involved, I had quite as good a time writing the story as John Doe found in reading it. Nobody does anything well without experiencing joy in the doing. I never plotted a story in advance in my life. I knew no more than the reader what Nick was going to do in the next chapter. So, I got fun out of it, recreation with the application. You’ve got to go at what you have to do with a whole heart, a clear vision, and with clean mentality. I never thought about my work from the moment I put it aside until I took it up again the following day. I rarely returned to it later in the day, and I never worked at night.

Second, I systematized the work, and I rarely permitted anything to interfere with the system. I got up at dawn. I do so still, every day, with rare exceptions. I ate a hearty breakfast. Newspapers or letters I did not look at. If a telegram came, it was opened and read for me. Unless it was imperative, I did not know of its arrival till later. I went at my work as soon after daylight as possible. I called eight hours of writing a day’s work.

Sometimes I wrote six or seven hours; sometimes I wrote nine. The length of the day depended upon the facility of the story, and please observe that I attach the word “facility” to the story, not to myself. An express train is often late, a hot-box or an obstruction on the track has delayed it. But it has to arrive to finish its work — and I had to write a certain number of words to finish mine.

Third, I was well equipped for that kind of writing — detective stories, so called. I was a lawyer, and had practiced law with some success. In the beginning when paying clients were rare, I applied to the judges in the criminal courts and requested “assignments,” which means that when a person charged with crime has no lawyer and no money to retain one the Court assigns a lawyer for the defense. One has to call at the Tombs, and Raymond Street jail and other places of detention, to consult with that class of clients. If you treat such a man “white,” and particularly if you are successful in his defense, he passes the information along; but it is treating him “white” and being strictly on the level with him that wins his everlasting regard, more than getting him clear, for very often he hasn’t a shadow of defense, and knows it. Before I realized it, I had a paying criminal practice — and I knew as many crooks as a headquarters operative.

Again, I had traveled nearly all over the world. I had met, and known, all kinds and classes and conditions of men and women, and wherever I went I made it a point to meet and know them, and to make them like me. I had worked on newspapers as police reporter, general reporter, special correspondent, and at differing editorial desks, and had acquired, thus, another angle of cosmopolitan education. I was Washington correspondent through parts of two administrations, and I had not let that opportunity for assuaging my insatiable thirst for general information get past me without mopping it up. I got to know, personally, and often intimately, so many senators and congressmen and officials and public men generally that when I glance back at my old notebooks it amazes me.

My appetite for superficial knowledge was always voracious. Whenever I struck a new town I sought the streets, and the purlieus, rather than the parks and churches, boulevards and museums, libraries and art galleries. The only public buildings I cared to investigate were the courthouse and the jail. I was never a gambler, for greed, or for excitement, but I had a passion for visiting gambling houses and knowing gamblers. I have known scores of them from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and there was never a time when I couldn’t “get in,” even when “the lid was down,” notwithstanding the fact that they knew I didn’t play — not what they call “play.” As a matter of fact, they liked me the better because I did not.

Also, I developed a passion for being “taken through” all sorts of factories, and talking with the workers: rolling mills at Pittsburgh, thread mills at Willimantic, lead-pencils, saws, files, paper mills, knitting mills, woolen mills, shoe factories, machine shops, dairy products, stock yards, packing houses, ship yards . . . . You would see me headed for such goals pretty soon after I hit a new burg — places where they made things! And yet have no mechanical gift or taste. I know about as much about mechanics as a hog knows about skating. It was the worker I wanted to see and to know. The men and women and boys and girls who toiled in such places; and I would not swap some of the friends I’ve made in that manner for all the high-brows on earth.

That brings me directly to the gist of this whole subject. If you want a rule to go by for producing (whether it’s writing thirty-three thousand words or more a week about Nick Carter, or selling wares, or putting up a proposition, or succeeding in anything you undertake to do) I can give it to you in two words. Here it is: Know PEOPLE . . . . all people! every kind of people! all sorts and conditions of people! Know them in the street, in the workshop, in the drawing-room, on the tail-end of surface cars, and straddling between platforms of subway or L cars. Play pool with them in firehouses; chat with them behind the.hotel desk, across a counter, punching tickets, making the ferryboat fast in the slip. They are all human, intensely human, and that is what you need to know — humanity.

I have mentioned only men, but I mean women, too. They are just as well worth knowing, and just as easy to know. And they will not resent your knowing them if there is nothing in the back of our own mind to make them resentful. That is up to you. And you can’t put it across if there is anything of the sort in the back of your mind. You can’t hide it if it is really there. In getting acquainted with Humanity it is essential to know women as well as men. Every man works to help some woman; every woman works to help some man — mother, father, sister, brother, wife, husband, sweetheart, offspring. It may not always be in dollars and cents, but it is always help, in one form or another. You must absorb superficial knowledge of both viewpoints in order to attain to excellence in any calling. Put that into your pipe and smoke it!

In the days when a string of truck-gardeners’ wagons en route to Washington and Fulton Markets plodded down Fulton Street, Brooklyn, from East New York to the ferries, between 1:00 A.M. and daylight, I loved to ride with the drivers, and chat with them. And I mean chat. Don’t ask prying questions. Begin by telling something. Tell a story about a child, or a mother; better still, tell one about your own mother. Abjure profanity. Vulgar and profane words never get you anywhere in anything. Don’t talk much. Venture a bit of information observed by you in another community or country upon the business that he is engaged in; then shut up.

When making sea voyages I always seek the assistant engineers — and I see that vessel from stem to stern, and from keels on to upper deck, and talk with the men in every part of it, before port is made. I have ridden in locomotive cabs on nearly every railroad in the United States and Mexico, and many in South America, at one time and another. I have spent days at a time in the coal mines at Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, in the silver mines of Nevada, in the gold mines of Colorado, and I have gone through sulphur mines in Mexico. That wasn’t pleasant! I went to the top of Popocatapetl as the guest of a Mexican governmental engineering outfit (eighteen thousand feet) and sat in the sling and was lowered thirty meters down into the crater over the water that covered the deposit of sulphur at the bottom of it, several hundred feet beneath me. That wasn’t pleasant, either; but I wrote a Nick Carter with that scene in it, later.

I rode several miles down a lumber chute in a V-shaped “boat” in Nevada, once. I wouldn’t do it again for Mister Croesus’s bank account. I went down to the bottom of the North River in Professor Tuck’s submarine called “The Peacemaker” in 1880-something. We did not go anywhere else. We just stayed there three quarters of an hour, and — Tuck had proved that it could be done. The sub was a little thing, and looked like a “punkin-seed” fish, save for the coloring.

I never visited a factory or a mill or an engine-room or a stokehole or a harness shop or any industrial center, however big or little, to observe any part of the technic; I visited them to know the people who worked in them, and to acquire a superficial marginal knowledge of their work and their mental attitude toward it, and toward the rest of the world. I’d rather sit at the end of a river pier and whittle and chat with a longshoreman than to listen to the best platform lecture ever delivered. I make it a point, to this day, to stop and chat with “the cop at the corner” when he isn’t busy, and looks to be in a chatty mood; and I remember him and his name thereafter, and he remembers me and mine. I love to go out with the harbor police on their rounds. I have been made honorary member of three companies of the fire department. I never let a G. A. R. man get past me if I can help it.

Postmen are the most entertaining chaps you can imagine. Truck drivers and white-wings have families and homes and children and lares and penates, which they like to talk about — but you’ve got to be one with them (not of them) before they’ll open up. I visited “Beggars’ Paradise” in Hoboken once, years ago, and passed a night there studying panhandling as a fine art, and acquiring the slang. Talk about richness of expression! My, oh, my! The place was not overclean, but I enjoyed it. I have been cod- and halibut-fishing with crews from Cape Cod, and I have picked cranberries down there, too. I’ve been sword-fishing from Martha’s Vineyard. I have never been up in a balloon or an aeroplane — but I’m longing for an opportunity. (Aviators, please take notice!) I cannot give the entire list. It would be endless, because it means everybody in every walk of life where I have had opportunity to penetrate. (I was going to interpolate “high or low,” but there are no such things in everyday life, save as they exist in your own mental attitude; and if you have that attitude, you won’t get to the inside of things.)

I have been called a good “mixer,” but mixer isn’t the word. One must be “it” for the time being. If you are dressed better than the guy you talk to, you must make him “not see your clothes.” You must not use Harvard talk; you must talk his language. Jockey talk in the paddock, longshore talk at the river front, old-timer talk to the cop, because that’s what he wants to hear; and so on. Tom Byrnes, Alick Williams, George McClusky, George Titus, Steve O’Brien, and men in uniform unnumbered have been my personal friends. It has been the same with the firemen. I have made many friends in crookdom, and I have visited them, and done small favors for them, when they were “doing stretches.”

Any person, no matter who or what he or she may be, will like you and trust you when sure that you are not a double-crosser. George Cohan in a recent issue of this magazine gave a pretty good definition of being “on the level.” But he didn’t go far enough. On the level means being to the other fellow precisely what you would want him to be to you under the same circumstances. When he finds out that you are doing exactly that thing, you can go as far as you like. The sky and the center of the earth are the limits, and all space is the boundary.

Nick Carter was a detective because he loved to right wrongs, and to foresee and prevent them. He taught the principle that one must love one’s work. If you can’t love the thing you are doing, then love what the doing accomplishes. If there is no real joy in the actual labor, find joy in the consequences of it.

If you are asked if you can do a thing, say “Yes,” and do it. You can accomplish it through others if you cannot actually saw the boards and fit the pieces and drive the nails. Every man and woman and boy and girl and worker and idler and lawmaker and lawbreaker whom I had seen and talked to and hob-nobbed with helped me to write the Nick Carters. Every one of them performed part of that work for me, but under my direction — in the abstract.

Are you behind a counter, or in front of a steam hammer; or a trained nurse, or doing millinery? Are you a stenog, or a forewoman, or what-not? All right. Who pays you? How did they attain to the positions from whence they could pay you? Find that out. Take heed of the system. Three times out of five their beginnings were smaller than your own. Compel every human with whom you come into contact to like you, and to respect you — to recognize your eagerness to accomplish; willingness is not enough; you must be eager.

When you go to your room at night, after you have prepared for bed and are ready to extinguish the light, do this: Go to the mirror. Stand before it. Look upon the reflection within it. If you can nod your head and smile and say, “I have been square with you all day,” you’re all right. You will sleep well. You will do better work tomorrow. Don’t regret yesterday; that won’t get you anywhere. Don’t anticipate tomorrow; that won’t produce results.

Get busy when you wake up. Above all, get out of bed, the instant you do wake up — and go to that same mirror and nod and smile, and say, “I’m going to be strictly on the level with you all day.” Divorce yourself from alarm clocks. You can wake up at the right time if you want to do it. At breakfast, remember that gentlemen never willingly speak of disagreeable subjects. Make people around you smile; not at funny things, but because of pleasing ones.

I used to get thousands of letters from all over the world, from all sorts of people who sought suggestion for some form of betterment. I got one from Russia that was addressed to “Nick Carter, America.” There was rarely a letter which could not have been answered with the five words: “Know people, and be kind.”

With these few remarks —

No. There is one more point: The ego.

You’ve got to keep the ego in the mind’s eye all the time. Never let it get away from you nor dodge you — but don’t cram it down people’s throats. And always respect the other fellow’s ego. The hardest work on earth to do is to do nothing. The rich man who retires from active business to a life of idleness does not as a rule live long afterward. A Jewish friend of mine, a very old man, was once asked, in my presence, why he did not retire. His reply was very much to the point. He said:

“Because I don’t want to go to my own funeral.”

Here is the old Nick Carter signature:

Additional:

Wikipedia: Frederick Van Rensselaer Dey

Book foreword with brief bio

The New York Times obituary (paywalled)

* * *

In the end, Dey died penniless. It was a shocking and undeserved end to his brilliant and productive life. Especially so after reading his immortal and inspirational book, The Magic Story. It’s available in an illustrated edition at Google Books. I recommend it. At just sixty-three pages, it’s an exciting and fast read that will make you wonder and think.

Original page images (click to enlarge):